“It says here ‘conservation importance HIGH’ ” shouted Michael, reading from the folder of notes on Naiad’s restoration. “What?” I replied above the din of the angle grinder I was using to remove a rove from one of the nails that holds Naiad’s clinker planks together; suddenly the super-heated copper rove flew off and landed on the back of my hand. Michael shook his head; “Just be careful”. The first proper project that Michael and I have been given in the boat shed seemed to involve taking a boat to bits, rather that building it.

We had removed the thwarts and were now removing the old, damaged timbers from Naiad; one of few remaining Aldeburgh One Design dinghies built by Everson of Woodbridge. After removing the roves (carefully), one of us drove the nail through from the inside of the boat using a nail punch, while the other supported the plank from the outside and helped the nail out. Sounds easy, but we’re starting to expect complications with old boats, and of course many of the nails were bent, or inaccessible etc. so there was plenty to keep us occupied.

When we had pushed, pulled, coaxed and dug out enough nails that we could remove a few alternate timbers from one side of the boat (it’s important to keep enough in place to keep the shape of the boat intact), it was time for the exciting bit. I had previously imagined that a fair proportion of my time at IBTC would involve steaming wood into various interesting shapes, but it now seems apparent to me that steaming is very like painting, in that 90% of the time is spent in preparation and the main event is over in a flash.

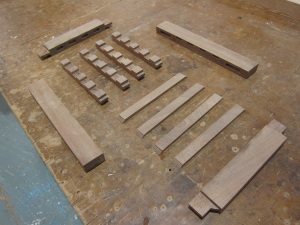

We fired up the steam box (a wallpaper steamer attached to a metal tube), and when it was hot enough, put our green oak timbers into the tube. Thirty minutes later, oven gloves at the ready, and Rob the tutor in attendance to make sure we didn’t mess it up, we pulled out our first hot timber. Michael bent it round his knee like an oversized piece of spaghetti and pressed it into shape inside Naiad’s hull while I screwed it into place from the outside; a temporary measure to allow it to take shape (the timbers will be nailed and clenched with roves later). We whizzed through our supply of timbers in the steam box and then stood back to admire our work. Now the process starts again; knocking out nails and scraping off old varnish and tar. There are plenty more timbers to replace, but at least we’ve put some of the boat back together.